The government has fuelled anger by tendering for new contracts. A Lords inquiry on translation services has further highlighted disquiet over low pay

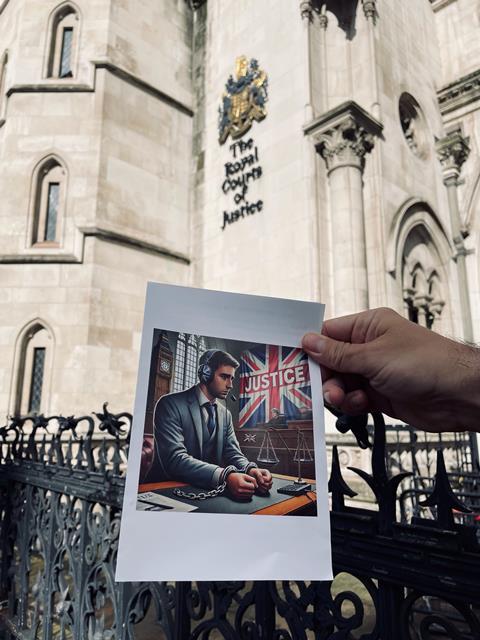

Twelve years after court interpreting services were controversially outsourced, the Ministry of Justice has once again incurred practitioners’ wrath by deciding to tender for new language services contracts.

Furious with the ministry’s decision to continue with the outsourcing model, court interpreters will refuse to accept bookings from language services contractor thebigword on 28 and 29 October – a move that could become a regular occurrence, spanning several days at a time, until they are invited to the contract negotiating table and offered better pay.

Next week’s action will be the second time interpreters have downed tools in recent weeks. They withdrew services for a week last month after problems with thebigword’s new booking system proved to be ‘the last straw’.

A spokesperson for thebigword said the company has a ‘great partnership’ with its linguists, an ‘open dialogue with our people about any issues raised’, and that employment lawyers have confirmed its contracts are appropriate for self-employed freelancers.

Now the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI) says it wants an external, independent review of the current outsourcing model. It has also questioned why the government is tendering for new contracts to begin in 2026 when a new framework is coming into force next October. NRPSI concedes the new framework is an improvement, as it raises the bar on the level of qualifications and experience an interpreter will require.

The MoJ told the Gazette it decided to continue with an outsourced model following an in-house assessment. To no one’s surprise, that internal document will not be published because it contains ‘commercially sensitive’ information.

The ministry added that the gap between the new framework and the new contracts will allow sufficient time for the tender process, approvals for the contract award and preparation for the mobilisation of the new contracts.

NRPSI is also puzzled as to why the ministry has not decided to wait until the House of Lords public services committee concludes its inquiry on court interpreting and translation services.

The inquiry got under way this week with the first oral evidence session. Highlighting challenges from solicitors’ perspective, the Law Society’s head of justice, Richard Miller, told the committee that many interpreters need to be funded through the legal aid system. Yet rates for experts have remained low and frozen for several years.

Miller said: ‘This has led over time to increasing numbers of all sorts of experts, including interpreters, [saying] they are not prepared to work for legal aid rates. That’s having an impact on the availability of some of the higher-quality experts, particularly in relation to the rarer languages, where obviously the market can dictate that you do need to pay a higher fee to get anyone at all who has the necessary skills. ’

Susan Grocott KC, co-chair of the Bar Council’s legal services committee, said interpretation needed to be re-evaluated: ‘They are very skilled linguists and we do see some exceptional people. They have studied and they are professionals. And yet they leave their current [employer] in droves because their pay, terms and conditions have not altered for the better in years and years. And it becomes unsustainable. They’re then “off contract”.’

To encourage people to become interpreters, Grocott said positivity is needed, including around terms and conditions.

She told the committee: ‘I’m a big not-for-profit girl as opposed to businesses which of course cream off the profits… I don’t see why any government contract shouldn’t have within its terms and conditions a commitment to automatically increase rates of remuneration. So, for example, if you had a seven-year contract, and the interpreter knew they would get an inflation increase, increases to subsistence in terms of travel and so on, they would I’m sure be interested in thinking that there was an investment and that they could become a linguist without eventually giving it up or doing it in a different way because it simply cannot pay the bills.’

Grocott added: ‘If it’s an hourly rate… but [the business] has no obligation to ensure that the people who work for them are actually taking a pro rata amount of that money consistent with their expertise, then that is a problem and those kinds of contracts shouldn’t exist.’

No doubt the committee will put Grocott’s contract suggestion to ministry officials when it is their turn to give evidence next Wednesday.

This article is now closed for comment.

1 Reader's comment